Editor’s Note: The following article was published before the devastating findings from the investigation into accusations of sexting, unwanted touching, spiritual abuse and rape by Ravi Zacharias. The continued publication of this article is meant as a service to our readers, and to provide historical context for his beliefs and ministry, and as a cautionary tale for the church. We were saddened to learn of his ongoing predatory behavior and how he used his position of esteem to cover up and further his abuse of many women.

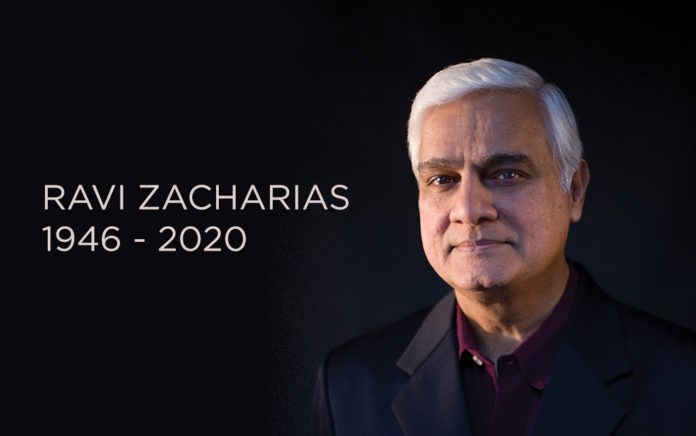

On Tuesday, May 19, 2020, Christian apologist Ravi Zacharias lost his battle with cancer and won the glory of God. He died at his home in Atlanta, at age 74.

Zacharias, founder and leader of Ravi Zacharias International Ministries, spent the past 48 years as an advocate for the Christian faith, tackling questions of origin, meaning, morality and destiny. He leaves behind a legacy of global ministry and a team composed of nearly 100 Christian scholars and authors who will continue to respond to the theological and existential questions of millions around the world.

As I was reflecting on the significance of his ministry to the church the past few days, I was reminded again of the much more personal impact he has had on my life. And my thoughts turned to my last interview with him, a few years ago, and how prophetic and appropriate his words are still today—in some ways, especially today. He was not just a champion for knowing and being able to articulate what we believe, but to convey the love, mercy and grace of Christ gracefully, as Saint Peter urged us in 1 Peter 3:15, and Ravi Zacharias modeled—with gentleness and respect.

Here in its entirety is that interview.

—James P. Long

RAVI ZACHARIAS: WITH GENTLENESS AND RESPECT

Ravi Zacharias was 17 when he decided to poison himself. It seems inconceivable now that he should have felt such intense shame over less-than-stellar academic achievement that suicide would present itself as an uncomplicated, even honorable way to avoid embarrassment and not bring shame on the family. To quietly exit life. But there, in his hospital room in India, an encounter with Jesus through John’s Gospel set in motion a series of events that now, a half-century later, has led him to be one of the world’s foremost champions of thoughtful, intellectually rigorous faith. And to do so, he echoes the apostle Peter, with gentleness and respect.

“The Bible tells us to worship him in the beauty of holiness,” Zacharias says. “But when we present the gospel in an ugly way we disrespect and violate the very core of what it is we are trying to present. So with gentleness and respect we speak and present the coherence of all the answers of the gospel.”

For decades you have been in a position to influence the faith of many. What was it about faith that was first compelling to you?

The most important thing—the compelling aspect of my coming to Christ—in a sense is so different from my present call and ministry. But what happened prior to my coming to Christ is probably more reflective of why I’m in this kind of ministry. I had lots of questions. I had a lot of struggles. I was immersed in religion on every side. My ancestors came from the highest caste of the Hindu priesthood, but somewhere a few generations ago a conversion took place, and so we were nominally Christian. I would attend an Anglican church with my parents in Delhi, but I never felt any impact of any one of these religious worldviews in my life. It was just a culturally accepted thing. So I had so many questions and was probably more a skeptic deep inside than anything else.

But at the age of 17, when I tried to take my own life, on a bed of suicide, someone came into my hospital room with a Bible and opened it to John chapter 14. He had my mother read it to me, because he was not allowed to stay. I was in such critical condition.

To hear the words of Jesus in the 14th chapter of John talking to Thomas, not just saying, “I am the Way, the Truth and the Life,” but going on to say, “Because I live you also shall live”—to me, the idea of what living actually meant was what I needed to come to terms with. And I found that in Christ.

As I look back upon it, the fact that the Lord cared enough about me in my total state of desperation to have a person bring a Bible into my room, and then finding Christ as my savior—in hindsight, I think that was the most compelling thing. When all else failed me, he was there like the Hound of Heaven. At that time as a man desperate, I wanted life and he offered it.

As life unfolded and you faced questions, struggles, challenges, what kept you convinced?

What kept me going? Two things: The transformation within every member of my family, especially my father who was so hostile toward my initial response of the gospel and was very hard on my mother and the family. He was a man the transformation in whom was indisputable.

My wife said to me one day, “Looking at his photographs I can tell you when the change came in your dad’s life.” That’s how dramatic it was.

And I saw the impact of my own testimony upon all of my friends—Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists, Sikhs. Prior to my coming to Christ I don’t know if I knew a single person who had ever shared the gospel with me. But I did not have a Christian friend. They were all from other faiths. To see the impact that my transformation had upon them showed me how they themselves were searching, they themselves were hungry for the truth.

And then following it up with a disciplined life of reading some of the great authors—I would say that was probably the most important thing. I was a voracious reader of biographies—the life of William Carey, C.T. Studd, David Livingstone, Adoniram Judson, Amy Carmichael, Annie Johnson Flint. And fire begets fire.

We don’t know the questions or difficult experiences we may face tomorrow. What gives you confidence that faith will be adequate for any unanticipated experience you may encounter?

That’s a very, very sobering question. I think it was Peter Kreeft who wrote that Christ is not only a provider of answers in propositions, but a provider of answers in his presence. In the presence of Christ we find that there are some questions for which the answers are going to be relational.

That’s how we grow up as children. That’s how we find our security, even as infants. We trust the person—as a result of that, the presence of that person makes a world of difference, even in the midst of pain. Now to a child, of course, there’s very little descriptive context. But to the adult Christian there is a descriptive context. The Christ who has answered our fundamental questions of origin, meaning, morality and destiny, comes to us in our greatest need and establishes that relationship with us.

Through an understanding of his teaching and his presence you begin to know that some answers are propositional, some answers are relational—they’re not antithetical to each other, neither does it jettison reason, but you realize that many times in life the answers are found in the knowledge of a relationship. I have absolutely no doubt that the God who met and transformed me more than 50 years ago is the God who will carry me through into the future, sometimes with answers that are clear and sometimes with answers that are in his presence.

Is there a greater interest in apologetics now than at other times in your ministry?

Going back, there have been legitimate fears the church has had about apologetics. Ultimately, the transformation of a heart is not done by reasoning. It is done by the enabling of the Holy Spirit. Only the Holy Spirit can convict a person of truth and bring them to the point of recognition that they need a Savior, and that this is a matter of dealing with your own pride and arrogance and self-reliance. C.S. Lewis is right: Pride is the ultimate sin that brought Lucifer’s fall. So apologetics can become a very dangerous enterprise if somehow the apologist thinks he or she can argue somebody into the kingdom. And if you do, then someone else of course argues them out of it, and it’s not so much a work of God as it is a work of man. So there were legitimate concerns about apologetics.

But there were illegitimate extensions made by it for which we are now paying the price. When Francis Schaeffer and others were doing their writing in the ’70s and ’80s they were warning us where all this was headed, where culture was headed. If you could just read the books of Schaeffer and C. Everett Koop and Malcolm Muggeridge and Lewis and others before them.

Lewis’ Abolition of Man is one of the most prophetic books ever written, I think, and it was written in the mid-1930s.

He saw how language was changing because it was trying to eradicate concepts. How concepts would then bring in a different worldview, and how science itself would align into a scientism and a kind of explanation of everything. While on one hand natural law was being done away with, naturalism was taking over.

All of this was taking place, and what did the church do? We abdicated our responsibility. We did not deal with our young people. We did not answer their questions. So they were going to university, and within the first year they were being vanquished by counterarguments. So we made a big blunder in not answering the questions and not responding to the issues, and I think that’s why a rude awakening has now taken place—a resurgence of interest in apologetics.

The church is awakening to the need and our young people are under immense threat. I would go so far as to say if we do not recognize that’s happening now at an earlier age—with 11-, 12-, 13-year-olds—the concept of the gospel will be totally foreign to the Western world and totally mythical in the next generation. The actions we would then have to take to reverse that would require generations.

So apologetics must matter to the individual Christian and to the Christian community. It’s not enough to just experience faith; we must be reflective about it. So how would the church be different if it embraced this responsibility more completely?

You know, C.S. Lewis’ comment is very appropriate. He said, “The question is not whether you are doing philosophy or not. The question is whether you are doing it well or doing it poorly.” Apologetics is being done. The question is, are the reasons we are giving for the hope within us truly the reasons that meet both the mind and the heart, and are we doing it in the proper way, with gentleness and respect?

The church of today would not look like it does if we had done our apologetic and theological homework.

Let’s look at basically where we’re headed in many churches. We look at an extreme form of very high programmatic successes—not to minimize it; I think it’s important. But the program is meeting every need but the intellectual. Then you know it has actually blundered reason and is going purely on experience and the aesthetics and delight of our faith experience.

And then the second thing we see is where the fundamentals of the gospel have been compromised. In the process, you get churches that are priding themselves in high success, and yet the gospel story is never told there. The cross is never featured in preaching. Where the Gospel of John has more than 50% of it on the passion of our Lord, that has to tell you how critical it is for our belief and evangelism. Yet when you don’t hear it proclaimed and preached, then you know the gospel has been lost and some form of an ethical cultural alternative lifestyle has been created where people just want to believe some nice things and feel comfortable in it.

How do we speak into volatile cultural issues in a way that does not further alienate the church from culture, even as we seek to speak a corrective word? I’m concerned about the church’s role in a polarized culture.

You’ve raised a very critical issue for our times. And you know the old adage, “Any stigma can lick a good dogma” holds true. If the church is stigmatized as a body of prejudice, if the Christian faith is seen as that which pejoratively speaks of people in what they want to hold onto or value, they’re really not going to listen. It’s quite remarkable that Christ never specifically addressed some of the burning issues of the day socially. He always went to the heart of what separated a person from God and what transformed a person so that they would think their thoughts after him.

We have instead gone to the symptomatic issues and have lost track of the fundamental issues. And the more we go to the symptomatic issues, the more we produce prejudices and discomfort and wrong solutions to the maladies. We have sort of walked out of arenas that needed our voice, so we left the academic arena, we left the defense of the Scriptures—all of this—and started attacking cultural moods and trends, and we end up thinking we’re winning a battle. We lost the war. We have to be laser sharp on what it is that really needs to be addressed in our times. That’s the first thing.

The second thing is, some things are discussable in a public arena without risk. Others, no matter what is said in that public arena, it ends up losing the bigger cause.

So I often say of great social issues—not that they are unimportant—this is not the setting in which I want to talk about it. If you want to discuss it, let’s sit around a table so that at the end of it, even if we disagree with one another, we can shake hands or give each other a hug and say truth will triumph in the end. But if I gave you an answer in this public setting, you’re not going to be able to counter it, you’re not going to be able to tell me what’s on your heart, and we’ll walk away creating a bigger wall between ourselves.

My mother used to say, “Once you cut off a person’s nose, there’s no point giving them a rose to smell.” We’ve done a lot of nose cutting the past few years. Not that the issues weren’t important, but I think they would never solve the heart of the problem. We’ve made everything a moral issue and forgotten that the salvation message is what morality alone cannot solve.

Let’s talk about a couple specific issues, one intellectual and one moral, and tell us how you would advise the church to deal with them in a way that is less combative, more constructive. First, creation vs. randomness, chance and materialism.

Galileo made a famous comment: “The Holy Book tells us how to go to heaven, not how the heavens go.” Sometimes we want to take the Bible and try to make it what it was not intended to be—some kind of a finer text in the specifics of how all this was done by the Creator.

It’s fascinating that science thrived under people like Newton and Faraday—they were believers. But because they believed in a design, because they believed in order, because they believed in predictability, they didn’t believe in a random universe. They believed in order and laws and design, and what naturalism has done is taken the laws and order and design as an end in itself rather than a means.

The church did away with the legitimate expressions of science and where they needed to be and made the Bible a book of what it was never intended to be in its specifics. The Bible deals with my heart and my soul and what God has provided for the most hostile aspect of my life, which is my own proclivities, my own will.

Rather than spend our time debating for hours whether its billions of years or whether its thousands of years, we should instead start by arguing for the fact that you cannot explain the full questions of life—origin, meaning, morality and destiny—without a personal, moral, First Cause, which is God himself. We go to the ultimate cause, not the ultimate methods of how it all came about. You will never be able to get a coherent worldview without positing an eternal moral personal First Cause. That’s what I want to defend—I don’t want to argue a timeline.

I can recommend some great books. Seven Days That Divide the World: The Beginning According to Genesis and Science by John C. Lennox, my colleague at Oxford, is a brilliant book on dealing with where the issues here really lie. And people like Robert Jastrow urge us not to make the mistake of a scientific single vision.

If a person tells me science is all that matters. I generally say to them, “‘Should the scientist be honest in giving us his or her findings?’ And they just stare at me. I say, ‘Is that a scientific question or a metaphysical question, that the scientist should be honest in giving me his or her findings? That’s not a scientific theory, that’s a moral theory. That’s a moral pronouncement we’re making.’”

You cannot have a scientific single vision in this world. There has to be a convergence of the great disciplines—of cosmology, of theology, of history, of epistemology. All of these disciplines have to come to bear to explain the undeniable reality in which we live.

OK, let’s talk about a moral issue: homosexuality. How do we approach the cultural question in a way that reflects respect and builds trust yet maintains scriptural integrity?

I think we have to deal with the specific terms of what sexuality means. Let me put it this way in an illustration:

I had a television producer attend a series of lectures I did with Dallas Willard at Indiana University. She came from one of the major networks, and she was going to do a story on religion on the campus and planned to leave after five or six minutes of taping, but she stayed the whole time—three hours, the Q and A, everything.

And she said, “Can I talk to you?” As we were walking back she said, “You know, I appreciate what you say. I’m really doing a lot of thinking after your talk, Mr. Zacharias.” She said, “I have a question for you. Why is it you are against racism, which is a good thing—you are not racially prejudiced—but then you end up discriminating against the homosexual. How do you fit that all into the same picture?”

I said, “You know, I find it fascinating that in the first part of the question you talked about it as an –ism. In the second part of the question you talked about it as a person. But let me ask you this: Why are we against racism? We are against racism because race is a sacred thing. Your ethnicity is a sacred gift to you from God. Why do we make our decisions on sexuality? It is because sex is a sacred gift. That’s the reason we make our decisions on sexuality—the same reason we make our decision on race and ethnicity, which is a gift from God as is sexuality.”

It has to be treated in sacredness. Then I asked her, “Can you tell me why you treat race as sacred and de-sacredize sexuality?”

I said, “This is where we come from: We believe in the sacredness.”

There was a pause, then she said, “I just want to thank you for this,” and she shook hands and moved on.

So here’s what I think: We need to—from the pulpit and in our discussions—speak about the sacredness of sexuality. And any variation of it in the eyes of God becomes the de-sacredization of a gift from God that has its parameters and its boundaries.

Now having said that, we have to say to people, Do I look upon someone who has violated sexuality in a certain way as someone I’m going to hate? Or will I befriend and allow that person the right of their expression even though it’s not in keeping with mine, and believe that in the love of Christ and in the coexistence of society the work of God can do miracles in transforming hearts?

That’s the way we have lived through history. God gave a perfect law in the Old Testament and what happened? The whole system caved in because of the human will. No amount of law is going to change the person’s heart. It has to be the love of Christ and the proclamation of the gospel without making the person the object of that discrimination. We preach the gospel. We preach God’s values. But we must always keep the person in mind as the one God is caring for.

Is there one compelling apologetic? One best argument for faith?

I don’t think there is one compelling argument. In grabbing the finger of one argument you think you’ve grabbed the fist of reality. You run the danger of ignoring everything else. And we run the danger of making it an intellectual thing.

The best way I could say it is there is a confluence of all the answers of Christ to the manifold longings of the human heart, to borrow a phrase from C.S. Lewis. If the individual by definition is indivisible—going back to the Latin—then there is the heart, the mind, the passion, the longings, the hungers that go deep within the human heart. They are all answered in Christ.

Archbishop William Temple defined worship as the submission of all of our nature to God—the quickening of conscience by his holiness, the feeding of the mind by his truth, the purifying of the imagination by his beauty, the opening of the heart to his love and submission of will to his purpose—all of this gathered up in adoration is the greatest expression of which we are capable. All of the longings of the human heart find their optimal expression in Christ alone.

I was asked to speak at the United Nations Prayer Breakfast on the search for absolutes. I said, “Let me just tell you the absolutes we look for in four areas: evil, justice, love and forgiveness. We want to define evil. We want to define justice. We want to define love—and when we blow it, we know we need to be forgiven. We’ve all experienced this.”

And I said, “Let me ask you this now: Where is the one place in human history that the four of these came together? They came together on a hill called Calvary, where evil was seen for what it was. The justice of God was at work. The love of God found its expression, and the forgiveness of God was offered to all of us.”

This is the one argument: Christ pulls together all of the longings of the human heart and the provision that God has made to make life coherent.

For more information about the findings of the investigation into accusations against Ravi Zacharias, click here.