Editor’s Note: The following article was published before the devastating findings from the investigation into accusations of sexting, unwanted touching, spiritual abuse and rape by perhaps the foremost Christian apologist of his time, Ravi Zacharias. The continued publication of this article is meant as a service to our readers, and to provide historical context of his beliefs and ministry. We were saddened to learn of the inconsistency in his personal life.

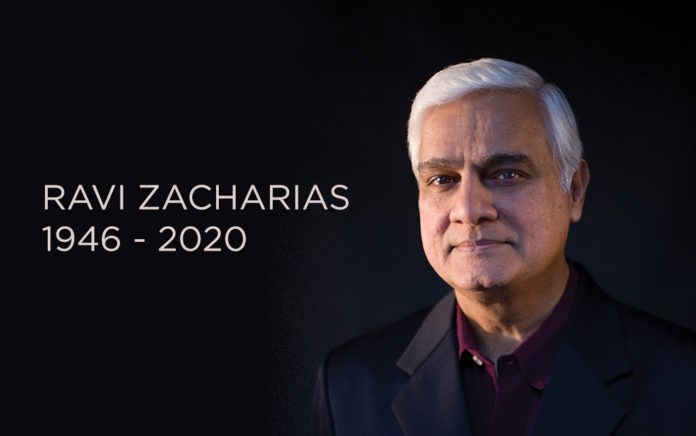

In the early morning hours of May 19, 2020, surrounded by his immediate family, including his wife Margie and their three children, Sarah, Naomi and Nathan, Ravi Zacharias went home to be with the Lord at the age of 74.

When we were asked to contribute a chapter on the life and impact of our colleague and friend, Ravi Zacharias, in the forthcoming book, History of Apologetics, we had no idea that a year from then Ravi would be rapidly approaching the end of his natural life.

While the topic of our chapter reflected on his public ministry, Ravi’s Christlike character was even more evident in person than it was on any platform. Indeed, we have often wondered whether it was because of who Ravi was when he walked offstage that God kept putting him back on one. Never have we met someone so successful at what they do and yet so humble.

The reason that Ravi was unconcerned with his own honor was because he was consumed with giving honor to the Savior who rescued him. As he promised God in a hospital bed in Delhi at the age of 17, after a suicide attempt led to a dramatic conversion to Christianity, “I will leave no stone unturned in the pursuit of truth.” What Ravi came to discover is that, ultimately, truth is not a proposition; it is a person—Jesus Christ.

The state of Georgia, which Zacharias came home to every time he returned from frequent ministry trips which spanned the globe, is renowned for the lingering splendor of its leaf change in the fall. In those cooling weeks when summer fades to autumn, it is only as the leaves are dying that they produce the most glorious hues of all: red, orange, copper, gold. Just as in nature, sometimes that rare beauty can be glimpsed in the fading of a human life as well.

We witnessed this in our last interactions with Ravi prior to his death, as he expressed profound thankfulness to God for the gift of life that had been given to him: “I only gave myself 17 years, but the Lord gave me 57 more.”

Even at the end, when words became hard to form and there was little strength left to his voice, there was one word that Ravi mouthed with fervency and conviction, over and over again: “gospel.” To those who knew him best, it came as no surprise that this would be the word that lingered last on Ravi’s lips. As his wife Margie observed upon hearing him, “That is the man that I married.” In those final days, Ravi showed his true colors, and they were beautiful indeed. Commending to his hearers and those who would come after him the only legacy that mattered, Ravi spent his final breaths exhorting them to remain unwavering in their pursuit and proclamation of the only truth that turns death to life.

—Jo and Vince Vitale

Excerpted From

History of Apologetics

By Jo and Vince Vitale

Ravi Zacharias: Evangelist as Apologist

Considering both his origins and the trajectory of his life, Ravi Zacharias (1946–2020) was truly born “for such a time as this” (Est 4:14). Growing up in Delhi, India, Zacharias was influenced by a plurality of religious traditions, which uniquely prepared him for the 20th-century challenges of postmodernism. Likewise, his personal wrestling with questions of meaning and subsequent conversion as a teenager on a “bed of suicide” readied him to respond to the angst of existentialism. Raised in the storytelling East and trained in the philosophy of the West, the convergence of an Eastern methodology with a Western mind has enabled Zacharias to connect with audiences that span the globe and to bridge the distance between the head and the heart of his hearers. At a time when apologetics was considered a discipline for the academic and the evangelical church was losing its intellectual edge, Zacharias effectively combined apologetics and evangelism in a manner that continues to inspire the Christian and appeal to the skeptic. This culturally rich combination of evangelism and apologetics has resulted in Zacharias becoming one of the foremost evangelistic apologists of the last century.

Historical Background

On March 26, 1946, Frederick Antony Ravi Kumar Zacharias was born in the city of Madras (now Chennai), in the state of Tamil Nadu, South India. Ravi Zacharias was the third of five children born to Isabella and Oscar Zacharias, although Oscar, studying overseas, did not meet him until he was eight months old, a distance that contributed to the strained relationship between father and son.

While Isabella’s family hailed from Chennai, Oscar’s side traced their roots to Kerala. Zacharias’ grandfather Oliver, who worked at Madras Christian College, was the first Indian appointed by the British as an English professor. Despite these Southern roots, when Zacharias was a young child, his family relocated to Delhi for his father’s promotion within the Indian government. This promotion was the first of several, eventually leading to Oscar’s role as deputy secretary of India’s Home Ministry (the equivalent of the U.S. State Department). A child of the South in name, coloring and history, raised in the customs and languages of the North, Zacharias keenly felt this cultural dialectic, in which “[r]eligion, language and ancestral indebtedness are carved into the consciousness of every child of the East.” Despite their move from a one-bedroom home in Chennai to a two-bedroom home in Delhi, the poverty and suffering that Zacharias saw on a daily basis had a lifelong impact on him. He has described the gap between the prosperous and the impoverished, saying, “India is a nation of polarities of incredible proportions … the raw reality of life stares you in the face.”

As for religion, although Zacharias’ ancestors were Nambudiris—the highest caste of the Hindu priesthood—his family broke away from that lineage when Zacharias’ paternal great-great-great-grandmother was converted to Christianity by German-Swiss missionaries. But by the time Zacharias was born, the family’s faith had diluted to a form of nominal Anglicanism, putting them in the minority in the North, where the religious landscape is predominantly Hindu and Muslim. From the first time he saw a man lie down on his side to roll down a dirty street yelling out to God, Zacharias came to wonder whether religion was all “just superstition born out of fear, dressed up into a system and embedded into a culture.”

As for “Western” religion, as a child Zacharias found it equally incomprehensible. Despite the family’s nominal Anglican faith, the only lasting impression that church attendance had on Zacharias was his memory of the priest yelling at him for eating communion wafers, which he had mistaken for biscuits.

Likewise, despite being taught by Jehovah’s Witnesses who visited his home for a year and a half, Zacharias ultimately concluded that a faith that offered paradise to only 144,000 people held no hope for him. The one notable exception from Zacharias’ childhood was when his brother Ramesh recovered from a life-threatening bout of pneumonia and typhoid after a Pentecostal missionary, Mr. Dennis, interceded with the family before a picture of Jesus. Although that incident impacted Zacharias, it wasn’t until several years later, at the age of 15, that he seriously began seeking for meaning. His questioning was instigated by an increasing sense of such purposelessness. He remarks, “There were nights I lay in bed wondering if I was going to make it.” The search became more urgent after a friend died, and when Zacharias asked the Hindu priest scattering her ashes, “Where is she now?” the priest responded, “Young man, that is a question you’ll be asking all your life. And you will never find an answer.”

Zacharias discovered his first glimmer of an answer a year later when his sister became a Christian through the witness of Youth for Christ (YFC) and invited him to their rally. The second time Zacharias attended, although unclear on the message, he found himself drawn to the sincerity of the speaker, Sam Wolgemuth.

At the end of that meeting, Zacharias walked forward to receive prayer. But while a seed had been planted, it was not enough to overcome Zacharias’ escalating sense of despair. Although excelling at sports, Zacharias struggled to succeed academically. This displeased his father, who called him a “complete failure” and violently berated Zacharias over his academic performance: “His fears of my failure and my fear of him met in some very painful memories.” This tension came to a head upon his father’s discovery of Zacharias’ repeated absences from his premed degree at the University of Delhi, when Oscar beat Zacharias until his mother intervened. Summarizing his feeling of hopelessness at that time, Zacharias writes:

“If you have the idea that life is something random; that there is no point to it, no purpose; that you just happen to be here—in existential terms, that you are a useless being floating on a sea of nothing for whom in the end it all comes to nothing—then the idea of becoming nothing can seem better than that random something.”

To spare his family further shame, and himself further failure, Zacharias determined to take his life by swallowing poison that he had stolen from the university’s chemistry laboratory. The chemicals were so toxic that Zacharias instinctively began throwing up. A house servant overheard his cries for help and got him to Wellington Hospital. Unsure what the long-term damage from his suicide attempt might be, Zacharias was in the hospital with his mother for four days when Fred David, a director of YFC, brought a Bible with a verse highlighted for Zacharias’ mother to read to him. Given that Zacharias’ parents had kept the reason that he was in hospital a secret, Zacharias was shocked to hear his mother read the verse David had chosen—words spoken to the apostle Thomas by Jesus: “Because I live, you also will live” (John 14:19).

Those seven words impacted Zacharias so profoundly that they became to him “the defining paradigm” for his life. On that day he made a promise to God: “I will leave no stone unturned in my pursuit of truth.” In that moment, Zacharias experienced a renewed hope that drastically changed the course of his life. From then on, YFC became very significant for Zacharias. Under their discipleship, Zacharias found his lackluster scholarship transformed into a passion for reading Christian literature, from the works of missionaries to Bible expositors to his first encounters with Christian apologetics through C.S. Lewis and the British journalist Malcolm Muggeridge. At the same time, Zacharias transferred to the Institute of Hotel Management in Delhi and excelled there. Zacharias explains this newfound dedication as the outcome of seeing life “through a window of meaning. … Jesus wasn’t just the best option to me; he was the only option. He provided the skin of reason to the flesh and bones of reality. His answers to life’s questions were both unique and true.”

YFC was also Zacharias’ doorway into evangelism, particularly when at the age of 19 he won the preaching prize at the 1965 YFC Youth Congress in Hyderabad. That same year, Zacharias and four others established a YFC teen preaching team and travelled from Delhi to Calcutta, Hyderabad and Madras (Chennai) to share the gospel. During those 10 days, Zacharias preached 29 times and to his astonishment they saw hundreds give their lives to Christ.

Summing up those first experiences of evangelism, Zacharias notes, “I wasn’t sure of myself, but I was very sure of my message.” Observing the rapidly escalating impact that Zacharias was having as an evangelist, John Teibe, YFC director of Asia, cautioned Zacharias, “You will either make a very profound impact with your life and God will use you mightily, or you will be a colossal wreck.”

In May 1966, Zacharias and his brother Ajit were sent to Toronto, Canada, to prepare the way for the remainder of the family to relocate. Arriving with $50 in cash, Zacharias found work as the assistant to the banquet manager at the Westbury Hotel in downtown Toronto, and he began worshipping at the Yonge Street Alliance Tabernacle. It was at a Christian and Missionary Alliance (C&MA) youth symposium that Zacharias met Margie Reynolds, although on account of her family’s initial resistance to the relationship, they did not date until two years later.

Forming another youth preaching team, Zacharias continued evangelizing across southern Ontario, as well as studying part time at Toronto Baptist Seminary. Eventually Zacharias moved into full-time theological study, beginning at Ontario Bible College in 1968. Although Zacharias’ father initially struggled with this decision, not long after that, he also gave his life to Christ. While at theological college, Zacharias was approached by Ruth Jeffrey, a retired missionary, who arranged for him to go preach to the US troops fighting in Vietnam.

In May 1971 Zacharias landed in Saigon at the height of the Vietnam War and proceeded to travel across the country on the back of a motorcycle for three months through some of the most deadly war zones to preach the gospel to troops at military bases, the wounded in hospitals, the Vietcong in prisons, and to pastors and missionaries. For Zacharias, it was a disorientating experience of preaching to so many soldiers who were about to die and yet at the same time seeing the life-giving power of the gospel. Although “intensely aware I was unfit to be there,” throughout those harrowing months, Zacharias and his translator Hien saw over 3,000 people become Christians. The impact of that experience on Zacharias is highlighted by the fervency of his tone in a 1971 article:

“The need of the hour is an unleashing to God’s demands in total commitment—the need for a hunger and thirst after him—the disciplined prayer life—the willingness to bet their lives that Christ is—the call to give into his hands every area of their lives. This is what I shared with the youth as I traveled throughout South Vietnam. I found hungry hearts.”

This trip was definitive for Zacharias in confirming his calling: “I am an evangelist. I am called to do this—to be in places at risk, places where people are willing to hear.”

In April 1972, after graduating and getting married, Zacharias was invited by Reverend William B. Newell to be a district evangelist for the C&MA. Soon after, Zacharias began studying for an MDiv at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School (TEDS), where he was most influenced by his mentors in philosophy and apologetics, John Warwick Montgomery and Norman Geisler.

Reflecting on Geisler, Zacharias notes that he “inspired me with the confidence to walk into any lions’ den and believe I would come away victorious for the gospel. His best gift to me was his twin loves, the Bible and philosophy.” Zacharias’ time at TEDS also overlapped with William Lane Craig, who lived just two doors down in the same block of student housing.

From his second year of study onwards, Zacharias spent most weekends preaching evangelistically. During the summer of 1974, he was invited on his second extended overseas trip for the C&MA—this time to Cambodia, where the team again saw many give their lives to Christ. That same summer, Zacharias’ relationship with his father was also greatly restored after Oscar handed him a letter apologizing for the way he had treated him during his youth.

In 1977 Zacharias embarked on a 48-week preaching tour around the world after graduating from TEDS, this time with Margie and his young daughter Sarah. In total, Zacharias preached 576 times on a trip that began in the U.K. and ended in Hong Kong. Despite being one of the most challenging years of their lives, this trip confirmed Zacharias’ calling as an evangelist to the nations.

After two years serving as their national evangelist in Canada, in 1980 Zacharias was ordained into the C&MA and reluctantly accepted a teaching post at the Alliance Theological Seminary in Nyack, New York. This took place at the behest of Dr. L. L. King, who forcefully told Zacharias that “the call of the church is the call of the Lord, and we as a church are calling you.”

Overburdened with seminary classes while still preaching evangelistically on the weekends, Zacharias and his family describe that as one of the hardest seasons of their life. In 1983 Zacharias was invited by Billy Graham to speak at a historic gathering of four thousand worldwide evangelists in Amsterdam. Not only did Zacharias’ sermon “The Lostness of Man” leave a marked impression on his hearers, but the event proved to be catalytic for Zacharias as well.

Upon returning home, Zacharias was convinced that he needed to be in full-time evangelistic ministry and with great relief gave a year’s notice for his teaching role at Nyack. At the same time, determining that it would take around $50,000 to launch an evangelistic ministry tailored toward the thinking skeptic, the Zachariases committed to tell no one about their desire to start a ministry, nor about the financial need, but instead to pray. To their astonishment, a few months later at a conference, Zacharias was approached by a stranger named D.D. Davis, who shared that God had laid it on his heart to give Zacharias a gift of $50,000 for whatever purpose God was calling him to. Initially responding that he was uncomfortable taking such a large sum of money from a stranger, Zacharias suggested that they meet to discuss the vision before Davis decided whether to offer financial backing. Upon confirmation of Davis’ support, Zacharias asked what he would like in return, to which Davis responded, “All I want is your integrity.” With the assistance of D.D. Davis and other ministry partners, in August 1984 Ravi Zacharias International Ministries (RZIM) was established.

Theological Context

Zacharias’ theological framework was forged during an era in which truth was highly disputed both within the church and within the culture at large. As an evangelical seminarian during the 1960s and 1970s, Zacharias was strongly informed by what he describes as “the big break” taking place between liberal and conservative theology. On the one hand, many in the mainline churches had shifted from the liberal Protestantism of the 19th century to the neoorthodoxy of Karl Barth and Reinhold Neibuhr.

In conservative circles, on the other hand, a reactionary anti-intellectualism had become pervasive within evangelicalism. As Harry Blamires accurately predicted in 1963:

“The bland assumption that the church’s life will continue to be fruitful so long as we go on praying and cultivating our souls, irrespective of whether we trouble to think and talk Christianly, and therefore theologically … may turn out to have dire results.”

Reflecting on his student years in the early 1970s, Zacharias comments that “those were the days in which the evangelical church lost the universities.”

In place of critical thinking, there was a strong shift within evangelicalism toward the experiential. In Canada, Zacharias’ own denomination was impacted by the 1971 revival led by the Sutera twins. Beginning in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, it spread into Western Canada (including Ontario Bible College) and the northwestern United States. As part of that revival, students began walking up to the microphone in church meetings and publicly repenting. While the spiritual renewal was genuine, what concerned Zacharias and some of his peers was that such confessions were required from their fellow seminarians in the first place, rather than keeping short accounts with God.

Consequently, Zacharias felt caught in a tension between the assault of the mainline churches whom he saw as “hitting hard at the roots of our belief” and the evangelical churches who were abandoning their intellectual heritage to get “swept into some mode of the expressions.”

This struggle for theological truth and intellectual rigor within the church was compounded by the wave of postmodernism that arose in the West during that same era and which seeped into every facet of culture, from philosophy to the arts, through the latter part of the 20th century. To Zacharias, whose homeland of India is a seedbed of religious diversity, postmodernism was hardly a new threat: “I came amid the thunderous cries of a culture that has 330 million deities. I remain with [Jesus] knowing that truth cannot be all-inclusive.”

What concerned Zacharias was how the church, already caught in a “whirlwind of confusing signals, theologically and spiritually,” would cope with the surge of relativism and pluralism.

Zacharias’ unease was only heightened by the state of evangelism at that time. Televangelism was a new phenomenon, with the Jimmy Swaggart Telecast launching in 1971 and The PTL Club with Jim and Tammy Bakker in 1974. To Zacharias, this form of evangelism seemed insufficient for combatting the tide of skepticism, disillusionment and antiauthoritarianism that shaped U.S. society in the 1970s.

The turning point for Zacharias came at Billy Graham’s International Conference for Itinerant Evangelists in Amsterdam, 1983. While speaking on “The Lostness of Man,” Zacharias referenced Meursault, a character from Albert Camus’ The Stranger who, facing execution, informs the chaplain that although he does now know whether God exists, Meursault is indifferent to the question.

What disturbed Zacharias upon returning home from Amsterdam was the question of who was going to reach those, like Meursault, with a skeptical disposition of heart. Given that Zacharias had been asked to address his fellow evangelists at the conference as though he were preaching to 12-year-olds, the experience left him concerned that the church was ill-equipped to engage with the prevailing intellectual skepticism and spiritual apathy of the West. He noted that there were not many evangelists “who had the training or access to reach those opinion makers of society. The combination of a proclaimer and apologist was very rare, especially the cultural evangelist-apologist. … They weren’t reaching upward.”

Therefore, motivated by what Zacharias perceived to be the inadequacies in contemporary evangelism to engage the cultural influencers of the day, RZIM was founded with a specific intent to reach, with the gospel, the “intellectuals, opinion-makers, and ‘the happy pagan’” … a ministry that would communicate the gospel effectively within the context of the prevailing skepticism. It would seek to reach the thinker and to clear all obstacles in his path so that he or she could see the cross, clearly and unhindered.”

For more information about the findings of the investigation into accusations against Ravi Zacharias, click here.