According to Tim Johnson in his book, Crisis Leadership: How to Lead in Times of Crisis, Threat, and Uncertainty, there are two types of crises: incident and issue crises. Incident crises are like tornadoes, issue crises are like hurricanes.

I’ve had experience in both tornado and hurricane environments. They are both scary, nonetheless. In any case, you seek shelter in both types of turbulent storms.

In the case of tornadoes, experts say one of the best places to seek shelter is in a basement. While I’ve lived through plenty of tornado warnings, I’ve been fortunate to never have one hit my home. However, I’ve seen plenty of pictures and images from friends and news stations of the damage that tornadoes have caused.

Seeking shelter from the force of hurricane is very similar. However, if meteorologists are predicting a more powerful hurricane—like a category 4 or 5—many choose to seek shelter more inland. In other words, they leave their home and their area all together.

After the storms hit, people emerge from their basements (or bathrooms) or from their parent’s house in Georgia (where they fled), to assess the damage. After assessing the damage, they get to work cleaning up debris or fixing the damage. Typically, the severity of the storm determines the severity of work that needs to be done.

The above examples of seeking shelter, emerging from shelter, assessing the damage and going to work cleaning debris and repairing damages from tornadoes and hurricanes gives us a great image as crisis leaders for the process we will go through (and take our organization through) when crisis hits.

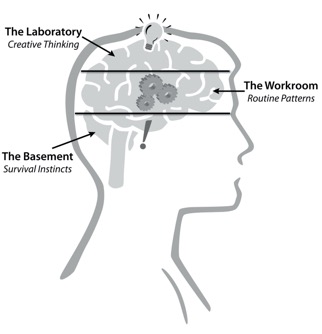

Borrowing from the authors of You’re It: Crisis, Change, and How to Lead When It Matters Most, I want to discuss how to lead your brain (yes, your brain) as well as your “braintrust” (aka, your crisis management team) so that you may lead your organization and yourself well through a crisis.

You can see above a picture of the brain. The authors of You’re It have highlighted the various “rooms” that will need to be navigated well during a crisis in order to exercise good leadership.

THE BASEMENT

I’ve been in those scary situations where you see the ominous clouds hovering over the house, hear the tornado sirens going off, and hear the meteorologist on the news station saying, “If you are in this area, you are in the path of the tornado. Seek cover immediately.” In those instances, your adrenaline rises, your heart begins to beat faster, and you react by gathering your family and going to a “safe” place—like the basement.

Nobel Prize-winning psychologist, Daniel Kahneman, explains that there are two systems at work in the brain—a fast and slow one. When facing mental challenges and complex problems, people use the slow system part of their brain. However, when they face routine or survival-like issues or incidents, they tap into the fast system of their brain.

The authors of You’re It describe the two systems this way:

“The routine circuits direct the learned behaviors that you do almost automatically. This includes your rote everyday activities, from how to walk and talk to riding a bicycle. … The other fast brain subsystem—the survival circuits—propels your instinctual behaviors. These include involuntary physiological actions, such as breathing and heart beating.” (94)

When a crisis hits, people’s brains instinctively move them into survival mode. Metaphorically speaking, people descend into the “basement” as an instinct to protect themselves. Psychologist Daniel Goleman technically refers to this survival instinct as an “amygdala hijack”—the amygdala being the part of your brain that processes emotions and serves as your threat alert system.

In the descent to the basement, people typically have one of three survival instincts as they react to threats, which would include crises. They either freeze, flight or fight.

It is important to keep this in mind when crisis hits—whether it is a gut-punch to your reputation as you read what people are saying about you or your church on twitter; whether it is a financial shortfall; or whether it is an active shooter on your organization’s premise. Your brain, as well as the brains of the people you lead, will immediately retreat into the basement by either freezing, fighting or flighting. This is natural, as it is an instinctual reaction based upon survival.

However, good crisis leadership does not happen in the basement! The basement is too emotional, it’s too simple, it’s too binary. The authors of You’re It conclude to “Never lead, negotiate, or make major life decisions when you are in the basement. The speech or decision you make when you are in the basement is the one you are most likely to regret” (98).

In order to exercise good crisis leadership, you will need to emerge from the basement and into the next room.

THE WORKROOM

When a crisis hits, your brain immediately sends you into the basement. How long you stay in the basement rests entirely up to you.

There’s a scene in Episode 1 of Star Wars, where the young Anakin Skywalker is in a very dangerous pod race. There’s a moment where his pod malfunctions and one of his engines lose power—threatening his chances of winning the race. Rather than freaking out, he remains cool, calm, and collected, and begins to flip switches and swap plugins in order to redirect power to the engine. In the end, he restores power to the engine and goes on to win the race beating Watto.

In order to emerge out of the basement there are some switches we flip and plugins we need to swap in the brain. There are at least three things you will need to do in the basement to emerge to the workroom.

First, you will need to remember your training (or remember your preparation). Leadership in the calm determines your leadership in crisis. In other words, if you are leading rightly when everything is going well, and you and your organization know your mission, core values, vision, structure, strategy, and crisis scenarios, then you have all the tools you to deal with this crisis—even if it isn’t one that you have specifically planned for.

Second, you will need to recenter yourself. The crisis knocked you down to the basement. You’re in survival mode—where your emotions are heightened. In order to emerge out of the basement you will need to recenter yourself by regaining your composure. Remember the defining characteristics of a crisis leader—cool, calm, and collected. How do you know you are recentered? You are able to breathe, you have a lower heart rate, and you aren’t driven by emotions.

Third, you will need to recite your “trigger script .” As defined by the authors of You’re It, a trigger script is meant to reset your brain by moving your brain from the survival side to the routine side of your brain (99).

There might be multiple kinds of “trigger scripts.” You might have a personal trigger script where you recite “God’s love isn’t based upon performance or what other people say about me” multiple times. Your organization may have a “trigger script” of saying “Code Red” in which you begin to follow pre-established protocols and procedures. For churches, when there is a financial or staff crisis, the trigger script may be “Let’s gather to pray.”

Doing these three things will mentally move a leader (and a group of leaders) from the basement into the workroom where they can at least begin the more routine cognitive patterns of working to remedy or navigate through the crisis.

I may add that many church leaders still find themselves in the basement as they are waiting out this pandemic, hoping that everything will go back to normal. Please listen: you cannot afford to stay in the basement throughout the duration of this pandemic. In fact, this pandemic is causing other kinds of crises. You need to get out of the basement and into the workroom! If not, when you do emerge out of the basement after all is said and done, you and your organization will be further behind and therefore less effective (missionally and ministerially) at navigating a new cultural landscape.

But even when you get into the workroom, there is still one more room to enter when crises hit.

THE LABORATORY

Crises, by definition—which we cover in our Crisis Leadership from a Christian Perspective Massive Open Online Course (or MOOC)—is when an event or issue begins to unravel order or threatens the flourishing of a person, organization, community, nation or world.

As I’ve mentioned above, when a crisis hits human beings instinctively enter into survival mode (the basement) where they emotionally either want to freeze, flight, or fight. However, good crisis leaders emerge from the basement into the workroom where they will begin the process putting things back together or eliminating the threat to their organizations by reminding their brain of their training, recentering their bodies to be cool, calm, and collected, and reciting their trigger script to begin the process of moving into the laboratory.

I’m not going to say much about the laboratory here. In short, the laboratory is where the creative thinking, planning, and execution takes place that either reorders what the crisis put in chaos or eliminates, or lessens, the threat the crisis poses to the flourishing of the organization.

Knowing the rooms of your brain you go to when crisis hits will allow you to lead effectively more than just a little bit.

This article originally appeared on The Exchange and is reposted here by permission.